By Rachel Bolstad

One possible challenge for anyone trying to get their head around the role of games in education is the semantics. Which words should we use to describe learning that involves games? What’s the difference between “educational games” “serious games”, “gaming”, “game design”, or “gamification”?

Game-based learning: An umbrella term

Game-based learning (GBL) seems to have emerged as a convenient umbrella term encompassing many different forms of practice. GBL can describe learning that involves playing games, designing games, analysing or critiquing games, or gamification [1]. GBL can involve games that are digital or non-digital, games that have been designed specifically with an educational purpose in mind, or the co-opting of commercial off-the-shelf games into an educational setting.

With all these variations, how important is it to identify, label, and classify different types of game-based learning practices? Or is it more useful to lump them together and talk about them as a general educational approach?

The answer depends on who you are, and what you’re trying to achieve. Precision and definition tend to be very important for some people, including researchers and academics. Researchers know that one of the first things one must do when setting out to study something is to define exactly what you are studying. Then, you ensure you’ve read around the literature to find out what other people might have already found in their research, so you know where your study fits in because nobody can ever study an entire area on their own.

There’s a lot to be said for defining and classifying concepts and trying to define their edges. It’s a great way to dig down deep into the core of an idea, and gain a deeper understanding of what that idea is all about. When it comes to games, a lot of ink has been spilled on the question of “what is the definition of a game?” or “what is the difference between a game and a [fill the blank]?[2]”. Inevitably, anyone who is interested in game-based learning must, at some point, engage with these kinds of questions, and read around in the literature to try to deepen their understanding of what games are, where they came from, what they do, and how they can be understood through different theoretical lenses. [3]

But there’s a downside to getting caught up with classifying and defining. I remember discussion at the Games and Media Summit at the 2015 Games for Change Festival. A whole day was devoted to looking at how games and other interactive media were merging together to create new and interesting things [4]. Were they games? Or interactive documentaries? Or gamified documentaries? Docu-games? Or... what were exactly? One of the keynote speakers[5] pointed out that maybe we should stop asking “is this a game or is it an interactive documentary?”, and instead ask “what is this thing and what does it do?”.

That made sense to me, and keeps coming back to mind when I think about GBL in the NZ classrooms we have visited, and some of the interesting differences between the literature-based view of GBL and the classroom-based view. I’ll try to explain this with an analogy about butterflies.

Typologies and butterflies

I recently read a helpful article that tidily mapped all of the common terms related to game-based learning into one neat diagram. The authors, Martí-Parreño, Méndez-Ibañez, and Alonso-Arroyo (2016) propose a typology for classifying game-based learning (they call it the ludification of education, the term ludus referring to games) into two main branches. On one branch there are games used for education, and on the other branch there is gamification. They further divide games into digital and traditional (i.e. non digital), and split digital games further into commercial off-the-shelf games, “serious” games (games designed specifically with an educational purpose), and authored games, meaning learners making their own digital games.

I’ve adapted and slightly modified it (blue text) below:

The point of this typology is to help classify different types of game-based learning, and to see how the different bits relate to each other, and to draw together findings from the various research around each of these types of GBL. Part of me finds typologies like this deeply satisfying: it reminds me of my undergraduate studies in evolutionary biology, and other fun scientific categorising things like taxonomies and cladistics and cladograms. But part of me also resists the drive to box things up too neatly (let’s not forget that for centuries, the Western colonial approach to classifying the natural world involved catching, killing, and pinning specimens to mounting boards in order to create tidy taxonomic order!). Scientific rigour and precision has its place, but life is infinitely more complex, messy, and interesting.

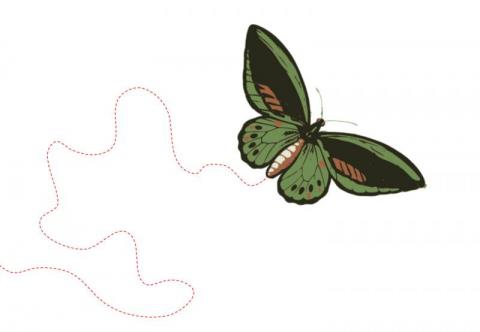

This brings me to butterflies. When I think about what game-based learning actually looks like in the schools and classrooms we have visited, it looks more like this:

In this image, the teachers and students are the living butterflies, moving peripatetically through all the different aspects of GBL. Sometimes they’re playing games, sometimes they’re making them. Sometimes they’re engaging with digital games, sometimes traditional games. Sometimes they are gamifying learning, and sometimes they are exploring what it feels like to be the creators and designers of games.

From this point of view the questions of interest relate to the butterfly and its wayfaring path.

- What shapes the course of that path? e.g. How does a classroom go from students playing board games, to students designing their own digital games, or vice versa?

- What curriculum and pedagogical intentions - and what unplanned opportunities or flashes of inspiration - shape the directions that GBL evolves in within any particular classroom or school?

- Is there one “best” way into GBL, or are there many different ways in, through, and around the GBL landscape?

And finally,

- are there things about GBL that we can only really understand by looking at, and sharing, GBL practices “in situ”?

A final word about the butterflies and their characteristic erratic fluttering pathways. Did you know that butterfly wings are much larger than they need to be? They're oversized in order to act as giant rudders, allowing butterflies to change direction, zigging and zagging to avoid predators. This ability to rapidly adjust movements in any direction is a clever little adaptation [6] that seems to be shared by many of the game-using teachers we have interviewed.

I’m looking forward to hearing Dr Bron Stuckey speaking about the breadth of value that games, game-based learning (GBL), game design and gamification bring to the classroom, at the upcoming Games for Learning conference. Her featured talk, “Rethinking who (and what) makes a game educational“, is sure to be be provocative, inspiring, and insightful. I hope to see some of you game-curious butterflies there!

Footnotes

[1] Gamification refers to the use or integration of game elements into a non-game context. Turning a learning activity into a challenge that involves wins or points, for motivational purposes, is one simple example of gamification.

[2] For example, interactive media, simulation, documentary, film, pick-a-path story, day in the classroom, etc.

[3] For example, try reading things about games written from the standpoints of psychology, sociology, educational theory, mathematical theory, literary theory, the list goes on...

[4] One interesting example was the documentary game Fort McMoney. See http://opendoclab.mit.edu/interactivejournalism/fort_mcmoney.html

[5] I think it was Nick Fortugno.

[6] Here's an online article on physics of Butterfly flight

Add new comment